Arthur Astor Carey House

28 Fayerweather St.

Cambridge, Mass.

Year Built: 1882

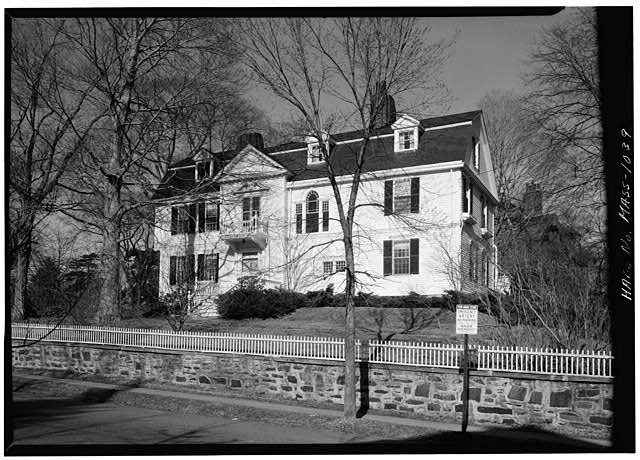

The Carey house is a large, 2½-story single-family dwelling that is covered with wood clapboards and trim which appears to be mostly original or dating no later than 1898. Except in the sunroom, the 12+12 and 6+1 windows and the blinds appear to be original or of the same early vintage, and are fitted with aluminum storm windows. The foundation is of smooth-faced ledgestone.

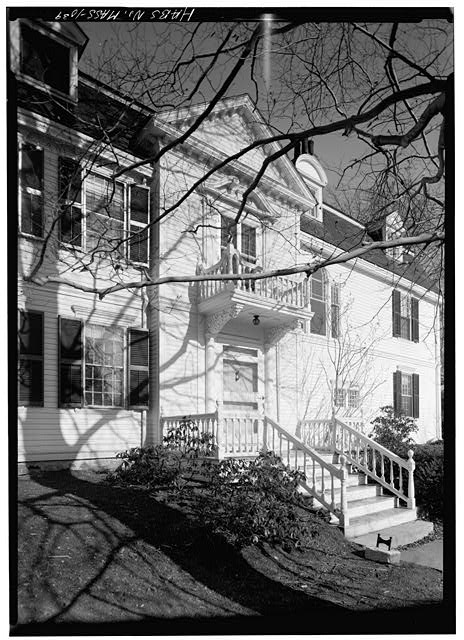

The exterior of the Carey house displays a number of Colonial-era architectural elements arranged in a somewhat unconventional manner. The main feature of the façade is an off-center pedimented frontispiece, in which the front door appears under an elaborate carved balcony. The balcony, which is supported by elaborate carved consoles displaying the carved heads of a man and a woman, is accessed by French doors set in a Colonial door surround with a scroll pediment. To the right of the balcony a Palladian window lights the stair hall, while two low windows light the space under the landing. On the left elevation, the second floor overhangs the first in the manner of a First Period house, while the gambrel roof has three narrow dormers, two with triangular pediments and one arched. Originally, the rear of the house had a sloping ‘salt-box’ roof, but this was lost in 1898 when rear of the house the house gained a 2½-story ell. The rear elevation now has two gambrel-roofed ells connected by a sloping roof. At the southeast corner there is an open porch about 12’ x 20’ stands on brick pillars about 5’ off the ground. A one-story sunroom was added to the north side of the house in 1988. The balustrade shown in an early photograph may have surrounded a sky-light, but these features no longer exist except as a flat portion of the roof.

The Carey house is significant as an early example of the Colonial Revival style in New England, the birthplace of an architectural style that dominated residential construction in the U.S. until the 1940s. The Colonial movement in architecture can be traced to the 1876 Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia. Following the divisiveness of the Civil War and the lingering effects of the financial panic of 1873, the centennial celebration fostered nostalgia for the country’s Colonial past. The exhibition’s inclusion of a New England log house and a Connecticut saltbox focused attention on the vernacular architecture of the period and increased interest in Colonial forms, particularly among architects.

The term “Colonial” in the 19th century encompassed many forms. Houses that drew inspiration and motifs from 17th century prototypes were often grouped with the picturesque Shingle Style, while houses that reflected Georgian ideals and displayed classical details taken from American and English

18th century buildings were labeled Colonial Revival. Equally rooted in the Colonial past, these trends developed contemporaneously in the 1880s and were often intertwined in the buildings of this period. Queen Anne and Shingle Style compositions often incorporated Georgian and other classical motifs, while Colonial Revival houses with more symmetrical Georgian plans sometimes showed a picturesque Queen Anne freedom of form or detail.

The Colonial Revival movement built on the early efforts of a few antiquarians to document threatened early buildings. John Hubbard Sturgis (1834-1888), the architect of the Carey house, was particularly active in one of the country’s earliest historic preservation struggles, the unsuccessful fight to save the 1737 John Hancock house in Boston. Sturgis had studied Georgian architecture in England, and his measured drawings of the Hancock house made just prior to its demolition in 1863 were the first of their kind in this country and opened the way for more accurate reconstructions of Georgian structures and details.

Two Cambridge houses designed by Sturgis and his partner Charles Brigham were based on the Hancock house and helped initiate the revival of Georgian architecture. The Edward W. Hooper house at 25 Reservoir Street (1872) and the Arthur Astor Carey house at 28 Fayerweather Street (1881) had gambrel roofs, central hall plans, and some interior elements derived from the Hancock house, although the overall massing and detailing were still influenced by the prevailing taste for the picturesque. Stick Style features on the Hooper house lessened the Colonial Revival feeling of the exterior, but the Carey house was much more explicitly Colonial, although the designer mixed Colonial elements in an unconventional manner.

Widely published, the Carey house has been recognized as a pioneering effort in the development of the Colonial Revival.

The lavishly appointed interior of 28 Fayerweather Street reveals how closely intertwined the Queen Anne and Colonial Revival styles were in the early 1880s. The large entrance hall, dominated by a massive corbelled fireplace, picturesque three-run stair, and quaint corner writing nook, was essentially a Queen Anne living hall, but the balusters and newels of the stair clearly reference the 18th century Hancock stairway. Architectural historian Margaret Floyd considered Sturgis & Brigham’s pioneering efforts in Cambridge to be as important to the formulation of the Colonial Revival movement as the better-publicized early work of Charles McKim, and with it Sturgis can be credited with re-introducing Georgian-derived details to Cambridge architecture.

References

• American Architect and Building News, 1/11/1890, No. 732, p. 23.

• "John Hubbard Sturgis," American National Biography, Oxford University Press, 1999, American Council of Learned Societies ("Edward N. Hooper (1872) and Arthur Astor Carey (1882), the earliest known Georgian Revival designs in the United States").

• Cambridge Historical Commission, Final Landmark Designation Study Report, Arthur Astor Carey House, 28 Fayerweather Street, 2012

Images

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

American Architect and Building News, 1/11/1890

<<< Back to Design List

|

|

|