Albert Burrage Mansion

314 Commonwealth Avenue

Boston, Mass.

Year Built: 1899

This house was built in 1899, and is on the National Register of Historic Places, named as a Boston Landmark and is part of the Back Bay Historic District. In this building, Brigham introduced staid Boston and New England to the lavish French Chateauesque style. Predictably the design was panned by contemporary critics, but the design has persevered and today is a Boston landmark.

The Burrage House was unusually wide for Back Bay, with the Commonwealth Avenue frontage measuring more than 55 feet. It was built to be completely fireproof, with a steel frame and terra cotta floor arches. Because of its steel-frame construction, the Burrage House did not have masonry bearing walls, which enabled it to have more windows than other buildings of a similar scale. L.D. Wilcutt and Son built the house for an estimated cost of $200,000 and the final building report was issued on January 11th, 1901.

With the design and construction of the Burrage House, Burrage and Brigham were aspiring to the opulence of Fifth Avenue in New York, where the Vanderbilts and Astors had built magnificent mansions in the chateau style. Several of these houses were designed by Richard Morris Hunt, whose designs for the Vanderbilts began in 1879 in New York and culminated in 1895 with the design for Biltmore in Asheville, North Carolina – the largest private house ever built in the United States. The Burrage House was inspired by Chenonceaux, a French chateau built in the Loire Valley between 1513 and 1521. Although Burrage may have hoped that his new mansion would set a standard for new construction in the Back Bay, nothing that was built after it rivaled it in terms of its design or scale. By the turn of the 20th century, a handful of vacant house lots remained in the Back Bay and what little new construction took place there followed the more conservative lines of the Colonial and Classical Revival styles.

Passing from the double-leaf street doors of bronze grillework backed with plate glass, you enter a vestibule leading to the main hall, which bisects the ground floor of the house. The use of such doors was a novelty and not in keeping with the original plans, as they were originally planned to be of wood only.

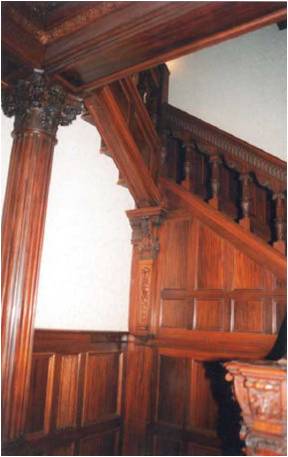

To the left (overlooking Commonwealth and Hereford, is the former drawing room, while on the right front is the former library. Running parallel with Commonwealth, the main stair, the treads, risers and banisters of which are entirely of marble, rises from the approximate midpoint of the hall’s depth. The stair is symmetrical in its configuration with double returns of ten risers each ascending from the landing (at the level of the 18th riser) which is lighted by an oriel with stained glass windows overlooking Hereford Street. Opposite the foot of the stair is a marble fireplace, flanked by paired semi-octagonal display cabinets of leaded glass, treated as oriels projecting from the wall. To either side of these is an apsidal alcoves expressed in carved and paneled mahogany. Beyond the stair and to the left, an anteroom opens to the parlor, which is oriented parallel to Hereford Street. The conservatory occupies the left rear (southeast) corner of the house and opens off the parlor, overlooking Hereford Street and Public Alley #430. Set within an elliptically arched alcove at the rear of the hall, a pair of double leaf doors open into the dining room, which also communicates directly with the parlor and conservatory by means of pocket doors. Ceiling heights in the first floor are 14 feet generally.

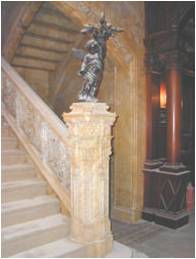

Ten feet wide and 15 feet deep, the vestibule is intended as a transition between the building’s exterior elevations and its interior spaces. Thus, the masonry expression of the exterior door surround is carried into the vestibule to a dimension equivalent to the width of each double door. A small stained glass window in the right hand reveal lights an alcove in the former library; this opening is balanced by a discreet door on the left which provided outlet from a stairwell (since demolished) leading directly to the principal bedroom on the floor above. Beyond this point, the walls are of heavily carved and highly figured mahogany paneling above a dado of green veined marble rising to the height of the eight-riser entry stair that spans the full width of the vestibule. Each of the vestibule’s side walls is configured as a pair of round-arched panels divided by a pair of pilasters, which break the entablature and are supported by marble plinth blocks. Similar, engaged, pilasters appear at the vestibule’s corners. Each pilaster is topped with alternating male and female terms (i.e., a pilaster, tapering to a narrow base and supporting a head or a bust of a mythological historical or grotesque figure above or in lieu of a capital); these are so arranged that those of the side walls face their counterparts of the opposite sex. The veneer panels of the side wall pilasters are interrupted at the mid-point of their height by foliate-carved roundels; similar half-roundels appear at the head and the base of the pilaster shafts. Mounted low on each panel is a shallow shelf, semi-elliptical in plan and supported by a console, whose surface plan with the base of the central pilaster roundel; above each arch is a blank oval cartouche flanked by putti and foliate carving filling the deep spandrel below the cornice. These carved motifs answer a broad oval cartouche, set within an eared panel, above the outer doors. Its frame heavily carved with scrolls and guilloches and flanked by addorsed mermaids bearing urns above disporting putti, the cartouche is lettered to read, “WELCOME YE COMING/SPEED YE PARTING GUEST,” stacked, as indicated, on two lines of copy radiating to reflect the oval outline of the oval cartouche. A beribboned trident, a device of Neptune relating to the mermaids, appears between the lines, functioning as an ampersand. Centered at the crest of the plaque is a low lobular urn while at its base a winged grotesque head appears. The vestibule ceiling is expressed as a segmental groin vault, whose diagonal ribs, rising from the engaged corner pilasters, are treated as narrow panels, producing an octagonal effect. All ceiling surfaces are of plaster grained in imitation of the mahogany below. The pendant light fixture that hangs from the crossing of the ceiling ribs is not original, but a hexagonal brass and glass fixture of recent vintage. Directly opposite the outer or street doors, a pair of double leaf mahogany doors similar in detail to the side wall panels but fitted with arched panels of glazing rather than the mahogany veneers of the side walls, lead into the inner or stair hall.

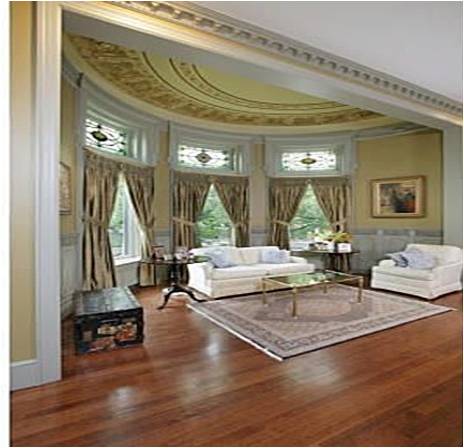

Little original fabric exists of the former drawing room, overlooking the intersection of Commonwealth and Hereford. Measuring 23 x 18 feet, the room’s principal feature is the nine-foot deep radius bay, lighted by three curved sash windows below decorative stained glass windows, at its north elevation. A single window lights the east elevation. The room’s original ceiling partially survives; areas of loss reveal the building terra cotta tile construction. Adamesque in feeling (making it more than 200-years later in inspiration that the exterior of the house), its central motif is an elongated ellipse, radiating about a rosette, enclosed by a rectangle defined by bands of laurel and beading, raised on a cove with vertical reeds of banded husks. Now soiled to a dirty ochre, the original ceiling may have been a straw yellow, enriched with pink and blue along its moldings of banded laurel. All colors have darkened with age and damage incurred through construction of later partitions and suspended ceilings (since removed), introduced to subdivide the room during its occupancy by the Boston Evening Clinic. The ceiling of the bay is lower in plane than that of the main room, being set at the spring line of the cove, but it is related in its detailing.

Like the drawing room, the library’s surviving historic fabric is limited to its fenestration and ceiling. The three windows of the alcove bay, set closer together than those of the drawing room, befitting the library’s smaller dimensions (19 x 14 feet) are set below decorative transoms of mottled stained glass. One is dedicated to astronomy, another to sculpture, while the third proclaims, “liber veritas,” (long live truth). The high dado surviving within the bay presumably existed throughout the room originally. It is also probable that the dado’s height, approximately six feet above the door, was intended to align with the cornice-level of bookcases, either built-in or free-standing, as would have been typical of late 19th century library decoration.

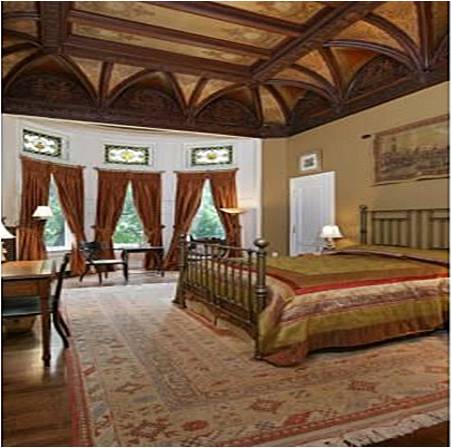

The ceiling is divided into narrow rectangular coffers whose ribs run east-west (parallel to Commonwealth Avenue), raised on a vaulted cove. The fields of the rectangular coffers are painted with conventionalized scrolls in shades of gold and brown against an olive ground; the browns relate to the coloration of the ribs of the coffers and vaults as well as the cornice. Subdivided vertically by minor ribs, the vaults’ pendentives are also painted with dense scrolls in browns and golds. Although the material of the larger members of the coffers has not been ascertained and may well be timber of some kind, it is evident that the rib vaults and cornice have been painted and grained to suggest a dark wood, possibly walnut or bog oak. Faux-painting of this kind also appears in the vestibule ceiling. Each vault opens to a lunette whose tympanum contains foliate scrollwork surrounding a tablet surmounted by a pair of putti holding aloft a laurel wreath. Each tablet is lettered with the name of a literary or historical figure; interestingly, given the exclusively European derivation of the architecture and decoration, these individuals are all American (e.g., Parkman, Lowell, Webster). More predictably, as one would expect during this era, all of the luminaries are white males. At the approximate midpoint of the room’s west, or party wall, elevation the vaults and cornice project forward, presumably to accommodate a chimney breast, since removed. The decoration of the room and the depth of the projection suggest that the former fireplace may have featured a hooded overmantel, typical of the late Medieval/early Renaissance period.

The parlor or living room is approached in processional fashion from an anteroom opening off the hall. An apsidal recess on axis to the double-leaf doors from the hall is lighted by a single window on the east wall, overlooking Hereford Street. The anteroom’s north wall (parallel and nearest to Commonwealth Avenue) is organized symmetrically with two door openings flanking a panel of boiserie. The right door is false, fitted with a single sheet of mirrored glazing, beveled at its edges, while the right-hand opening is fitted with a multi-paneled door of stained mahogany which connected originally to the drawing room at the left front corner of the house. The use of a single sheet of mirror rather than either a multi-light mirror or sham door seems somewhat surprising in relation to the paneled operable door. At the same time, the stained mahogan finish of this door and its more robust and notably un-French design, comparable to the decoration of

the entry hall or dining room, may well suggest that it has been reused from elsewhere in the house. Although the dimensions have not been compared, the anteroom door is certainly similar if not identical in design to extant and presumably original doors in the stair hall. Stained doors are proverbially incongruous in French-inspired rooms; as Edith Wharton and Ogden Codman, Jr., noted in The Decoration of Houses, “in France it would not be easy to find an unpainted door [The Decoration of Houses, page 58].” A paneled and painted door relating to the boiseries would have been more authentic to historic French models.

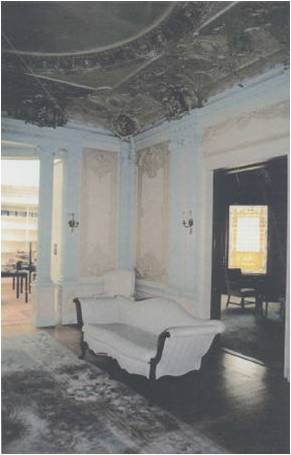

The decoration of the anteroom, which is 9 ft., 8 in. x 20 ft., is consistent with that of the larger (22-ft.-square) living room, to which it opens through a screen of untapered, stop-fluted Ionic columns in antis, raised on paneled plinths, to the right or south as one proceeds into the space from the hall. Though conceived as a formal French salon, a model favored for the parlors and drawing rooms of important American houses since the middle of the nineteenth century, the success of the living room’s décor is diminished by its anachronistic quality. Not only is it a room of eighteenth-century inspiration in a house whose exterior and other major rooms are derived chiefly from sixteenth-century Renaissance precedents, its commingling of Louis XV and Louis XVI motifs produces an unconvincing effect, suggesting it may have been a result of compromise. It is tantalizing to speculate whether this may have been between Mr. Brigham and Mr. Burrage, or between Mr. Burrage and Mrs. Burrage. The room’s rather severely neoclassical Ionic order, indicated in both the screen of freestanding columns and the companion pilasters that punctuate the walls, is uneasily overlaid with heavily scrolled Rococo-inspired boiseries and a coved ceiling organized into a pattern of low-relief arabesques enclosing a central circle. Scattered at regular intervals about the room, putti (detailed so individually and sentimentally as to suggest Valentine cupids) backed with cartouches perch restlessly on the cornice that divides the comparatively strict entablature of the walls from the more fancifully curvilinear geometry of the ceiling. A fireplace set between Ionic pilasters is centered on the east wall, flanked by a pair of tall sash windows looking onto Hereford Street. Louis XVI in style, the deep fireplace mantel is of white marble with convex-cornered, stop-fluted jambs enclosing a coved firebox opening of ormolu densely decorated with low-relief rinceaux. A trumeau mirror with gilt frame fills the space from the mantel to the entablature. Because the Louis XV elements on the east elevation are limited to the cartouche panels on the pilaster plinths, the more architectonic Louis XVI style appears virtually undiluted on the fireplace wall. Although it is thus the most successful of the elevations compositionally, its lack of relationship to the room’s other walls serves to undermine further the integration of the decorative scheme. Flanked by matching panels of boiserie, a pair of tall pocket doors occupies the living room’s opposite, west, wall, on axis with the fireplace. Much as the parlor’s east and west elevations reflect one another, the south wall’s freestanding columns in antis, framing a wide opening into the conservatory, echo the column screen of the north wall, which looks back into the anteroom.

The room’s skirting boards, columns, pilasters and entablatures are now painted a light pistachio green, while the fields of the wall and ceiling panels are painted a light putty; projecting elements of the boiseries are picked out in a darker putty. Apparently original, the circular center of the ceiling is painted to suggest a cloudstudded sky. The original paint treatment of the walls is unknown, however white enriched with gilding would have been more typical for a French salon in a house of such pretensions. Nevertheless, until such time as seriation studies might be undertaken the original scheme cannot be ascertained. The fact that there appear to be few coats of paint may suggest that the existing treatment is consistent with the original; the detail certainly remains very crisp as a result. The floor, curiously, is not parquet de Versailles, again as one might expect in such a room, but plain strip oak. The more convincingly detailed Louis XVI ballroom at the Walter Baylies house at 5 Commonwealth Avenue (now operated as the Boston Center for Adult Education), completed to the designs of Parker, Thomas & Rice in 1912, features both a white-and-gold paint scheme and parquet de Versailles flooring. The relatively humble floor material and design may suggest, however, that the original paint scheme was comparably simple (whereas gilded boiseries would have virtually presupposed the use of more costly and elaborate parquet floors).

The conservatory is the simplest of the ground-floor rooms. Its dominant feature is its ceiling, open to the roof, which is topped with a lantern of octagonal plan, both with convex glazing set within a cast-iron framework. The major ribs of the lower roof are supported by pilasters that break the room’s entablature. The diagonal ribs of the lantern’s upper stage are detailed with a pierced running scroll, lightening their visual effect. Three bays across its south elevation (parallel to the alley) and two bays deep (parallel to Hereford Street), the glazing of the walls was replaced at an unknown date with blind panels, stuccoed on the exterior. Framed-down one-over-one light sash windows have been introduced into all but the curved corner bays. While consistently aligned in relation to each other, the head and sill conditions of these later windows do not relate to the room’s entablature or dado elements. The glazing of the bays is to be restored to Brigham’s original design, evident in surviving exterior elevation drawings. On the north wall, a radius entablature thrusts into the room, supported by the columns and pilasters of the broad doorway opening back into the living room. Above and to either side of this feature, the walls are clad from floor to ceiling with coral, on which Burrage, a noted amateur horticulturist, raised orchids. The conservatory floor is not original, but unglazed terra-cotta tile of recent vintage, laid in a simple grid pattern, carried up the base of the walls for one course as a skirting.

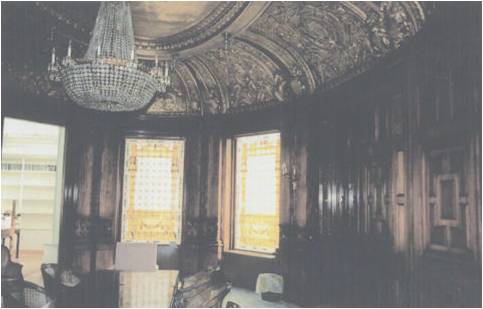

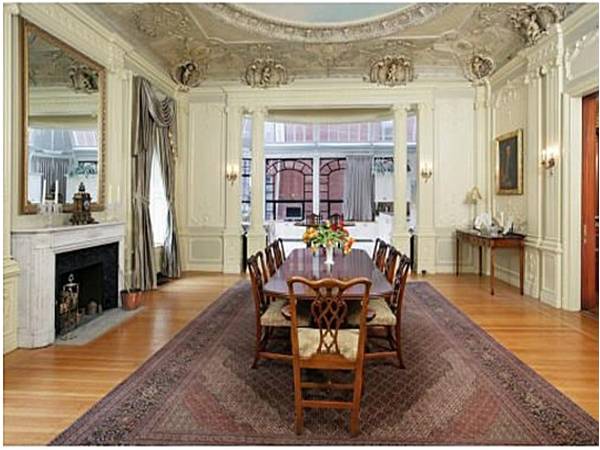

Closing the axis of the stair hall is the approach to the dining room, which also communicates directly with both the conservatory and the living room. Similar in feeling to the hall in terms of its stylistic origins and materials vocabulary, the dining room is elliptical in plan, measuring approximately 30 feet long (on the north-south axis) and 19 feet wide. Its location at the rear of the first-floor accords with a planning preference long established in Boston, from which little deviation appears to have been exercised in Back Bay houses. The room is lighted by two windows of stained and painted glass, joined by a leaded-clear glass pocket door opening into the conservatory at the left. The stained-glass windows are identical, featuring within an outer border of conventionalized foliate banding paired terms supporting an entablature surmounted by a broken-scroll pediment above an earpaneled base hung with a swag set within a pair of downward-tapering plinths, all in gold. The area between the terms is filled with geometric diaperwork, also in gold. The pocket doors to the conservatory share the outer foliate border and gold diaperwork overlay, but are in clear, rather than translucent glazing. The limited window area and its expression in stained, rather than clear, glazing probably reflects a number of practical and visual considerations. The restricted natural light may indicate that the room was reserved for the service of the evening meal, with breakfast and lunch served elsewhere (possibly in the conservatory, to which the dumbwaiter communicating with the basement kitchen would have been conveniently located). Stained glass windows frequently appear in the alley-facing rooms of Back Bay houses, as a means of admitting light while excluding an unattractive prospect. The block west of Hereford Street between Commonwealth Avenue and Newbury Street having been built up as commercial and private stables (Burrage’s own survives, in altered form, at 323-327 Newbury), the dining room windows were at risk for offensive odors as well.

The walls of the dining room are fully paneled, either in cherry or mahogany less richly figured than that used in the hall. The elevations are organized by pairs of unfluted pilasters whose capital and plinth carvings are similar, being generally of a Composite order, but of which no two are exactly alike. A rich frieze backs the capitals, supporting a simple cornice from which the coved ceiling springs directly, without an entablature. The paired pilasters support in turn pairs of mammalian-headed gryphons bearing blank armorial shields, above which paired ribs of gilt-plaster strapwork divide the cove into panels of further gilt plasterwork, in which large-scale scrolls and cartouches appear above pairs of addorsed avian-headed gryphons. Above the cove, the flat plane of the upper ceiling is configured as a long oval, painted and gilded to suggest a clouded sky at sunset, enclosed by a broad fillet about which pendant lighting fixtures, possibly original, radiate at intervals, centered on the pilasters. A large crystal chandelier of uncertain date hangs from a central rosette within the oval. Several gilt-bronze Rococo wall sconces exist in this room. As these fixtures, which trace their inspiration to the first half of the eighteenth century, are more than a century later in style than the room itself, it is believed that they originally existed in another room. As defined by the paired pilasters the walls are arranged in three tiers of panels to suggest the base, shaft and capital of a classical order. Centered on the long elevation to the west (parallel to the party wall), a fireplace once existed, of which only the firebox survives; its material and design are unknown. Following the removal of the fireplace mantel, the paneling on this elevation has been pieced and reassembled in a manner difficult to reconstruct and additional panels of lesser quality introduced to complete the scheme. Heavily paneled walls in cabinet-grade woods were favored in Boston dining rooms. Such rooms typically incorporated a built-in sideboard on the wall opposite the fireplace, a possibility precluded here by the existence of the pocket doors connecting to the living room.

The lack of a sideboard, compounded by the loss of the fireplace mantel, has left the walls of the room looking somewhat under-decorated in relation to the richness of its ceiling. Although the missing mantel (and, presumably, overmantel) may have been of different visual character, the style of the room’s surviving fabric suggests the heavy Italian influence of the first wave of English neoclassicism as introduced by Inigo Jones in the early seventeenth century.

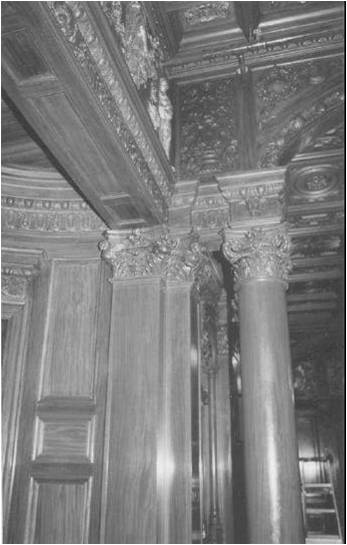

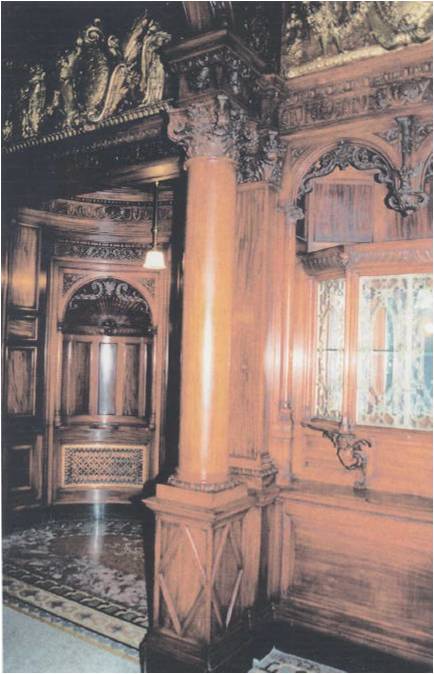

The great hall is the most palatial of the Burrage interiors, being both the largest, at 40 by 16 feet, and the richest in both material and detail. Similar to, though smaller in size than, the 63 x 18-ft great hall of the Ames-Webster house at 306 Dartmouth Street (as redesigned by John Hubbard Sturgis and Charles Brigham in 1882), the Burrage great hall also recalls that of McKim, Mead & White’s Boston Public Library, completed in 1895. Both are dominated by symmetrical, double-return stairs of tawny yellow Siena marble, however that of the Burrage house, in contrast to the Italian origins of the Public Library, reflects the lingering medieval character of the Northern European Renaissance. The space is arranged as a central atrium, with the staircase ascending toward the east wall balanced by the fireplace on the west defining the axis. Three elliptical arches, one of marble and two of mahogany, open off this focal area. The wood arches, which run transverse to the depth of the hall (or parallel with Commonwealth Avenue) are supported by unfluted Corinthian columns, raised on plinths each face of which is paneled in a vertical diamond, framed by coordinating pilasters. Leading back to the front entrance, a pair of double-leaf doors framed by pilasters matching those of the vestibule but raised on the diamond-paneled plinths common to the columns and pilasters of the hallway proper, is centered on the north wall. The doors are flanked by broad panels above the dado; below that line, ornamental grilles, presumably of polished bronze and worked in a diapered quatrefoil pattern, cover the outlets for heating registers. The skirting is black marble.

On the west wall, the central feature is the marble fireplace with its high (approximately 6-ft.) mantel shelf, and frieze carved with putti and scrollwork, supported by Corinthian pilasters. A slab of honeyed marble, unornamented but for its rich veining and a pair of torch-like, four-light bronze sconces, extends from above the mantel shelf to the base of the entablature, which is of mahogany. To each side of the fireplace is a semi-octagonal niche of paneled mahogany from which, mounted on consoles of winged putti springing from the dado rail, project display cabinets, also semi-octagonal in plan, below a gadrooned frieze. Each cabinet is fitted with doors of beveled and leaded glazing, a single glass shelf, and backed with mirror to reflect the objects to be displayed within. It is believed that Burrage used these cabinets to display choice specimens from his collection of gems and minerals. Supported on unfluted Corinthian colonettes to either side of each cabinet is a double arch spanning the width of the semi-octagonal niche.

From the center point of each arch hang addorsed S-scrolls of carved mahogany. Farther to either side, beyond the aforementioned groupings of plinth-mounted columns and pilasters, lie two alcoves, apsidal in plan. Each alcove features a decorative niche, whose head is a shell-carved hemisphere set within an outer arch hung with addorsed S-scrolls. Below each niche is a dado filled with a decorative bronze heating-register grille, matching those of the north wall in overall design but concave-curved in plane to follow the plan of the alcove. To the right within the far alcove (that nearer the rear of the house) and to the left within the near alcove (that closer to Commonwealth Avenue), is a door leading to a service core (originally containing a steel service stair, pantries and storage areas) running behind the fireplace wall along the building’s west or party-wall elevation.

The field of the hall floor is paved in mosaic tile of variegated light gray, laid in a wavy grid, while its borders are laid in more richly colored and patterned mosaic, with three principal decorative bands in ochre, salmon and sage green separating the flooring of the main hall from that of the alcoves. Set just within these bands is a slab of highly figured red marble, beyond which the remainder of the alcove floor is set with Pompeian-red mosaic worked with a bow-knot motif in cream, framed by an outer border of banded laurel in green and black mosaic. Minus the red-fielded semicircles and bow-knots, a similar flooring pattern exists in the alcoves to either side of the main stair at the east wall, opposite. The great hall’s frieze is executed in plaster as a series of vertical oval portrait masks, set within scrolled cartouches hung with wreaths and ribbons supported by male and female figures in sixteenth-century court dress, all gilded against a ground of mottled brown. The masks depict a variety of historic and literary figures, but apparently were chosen somewhat indiscriminately, as duplicates exist among the group of Pliny, Virgil, Dante, Shakespeare, and Cervantes. Although one Asian, Confucius, is included, none of the portraits memorializes a female, although several historical figures of the period (Elizabeth I, Mary Stuart, Catherine de Medicis and Isabella of Spain among them) would have been appropriate. The hall ceiling is coffered in intersecting octagons defined by deep mahogany ribs and filled with ornamental scrolls and cartouches in gilded plaster. Beyond a marble segmental arch the spring line of which aligns with the base of the column and pilaster capitals enframing the apsidal alcoves, rises a symmetrical, double-return marble stair. Centered on the heavily molded and carved lip of the arch a pair of putti flank a cartouche of heart-shaped contours. To either side of the stair are paired alcoves, walled in richly veined marble coursing, on each elevation of which is centered an arched door opening with carved surround and console keystone. Although some of these openings may originally have been sham doors, some probably led to closets or service spaces; it is evident that a pair of doors, one on each face of the lower stair run’s cheek walls, once opened to a passage to a basement stair. A stained-glass window at the landing of the basement stair was indirectly illuminated by a basement window at the Hereford Street elevation. The floor of the alcoves is laid in mosaic tile worked in diapered vines of buff against a Pompeian-red ground.

The stair to the second floor rises from west to east between paired newels of clustered pilasters, also of marble, at the level of the third tread (the first and second treads cascading around the cheek walls of the stair). The newels support bronze lighting fixtures in the form of putti bearing aloft electrified candle branches expressed as sprays of flowers springing from a pot. The banister of the closed-stringer stair is richly carved in the round with strapwork motifs incorporating gryphons, rams’ heads and putti amid panels of scrolls separated by baluster elements carved to suggest turning. These baluster carvings also appear in the newels, where they separate the clustered pilasters, and are incorporated in the exterior detailing as well. A landing with rounded corners occurs at the level of the eighteenth riser; above that point, paired upper runs of box treads return, running east to west, to complete the ascent to the second floor. Above a high dado of marble that rises to the level of the second floor, the landing is lighted by

an oriel, whose plan describes a shallow radius, with three flattened-arch windows. A pair of diminutive bronze sconces is mounted to the pair of Corinthian pilasters framing the oriel. Each of the oriel window depicts the stern of a sixteenth-century galleon in full sail flying the colors of (from left to right) England, Spain and France in stained and painted glass set on a blue sea within an architectural frame of gold in lead cames below a transom emblazoned with the respective country’s coat of arms. Above the landing, whose floor is mosaic tile similar to that found in the lower hall, hangs a heavy chandelier of bronze, while at the newels of the landing stand female and male marble figures in sixteenth century court dress. The male, at the right, wears a soft cap and flowing cape, and stares resolutely ahead while the mantilla-clad female on the opposite newel casts him a coquettish glance. It has been suggested, presumably on account of the female’s Spanish headdress, that these figures may represent Ferdinand and Isabella of Spain. As they appear to resemble no known portraits of those rulers and seem too conventionalized to represent historical figures of any kind, this suggestion is perhaps best regarded as a romantic notion.

On the walls of the stair cage above the second floor level, a blind balustrade continues the banister detailing, surmounted by marble coursing set within Corinthian pilasters matching the screen of paired Corinthian columns set atop the newels of the second floor landing. A marble balustrade, solid at its sides but carved in the round throughout its central section, spans the upper landing between the column-mounted newels. The columns and pilasters support a marble entablature enclosing wood coffers, which continue beyond the column screen into the second-floor great hall space. Set in a mahogany-paneled alcove to the left, within a pair of engaged, fluted Corinthian columns also of mahogany, a stair with base newel of clustered pilasters, closed stringers and banister of widely spaced colonettes rises to the third floor. The remainder of the second-floor hallway is taken up by mahogany doors and door surrounds arranged in an orderly and formally balanced, but asymmetrical composition.

Registries

• Local Historical District

• Local Landmark

• National Register

References

• "Revolution in Boston: A Historic Back Bay Penthouse Gets a Minimalist Perspective," Michael Frank, Architectural Digest, Nov. 2006, Vol. 63, No. 11, pp. 212-219.

• "When the Gilded Age Came to Commonwealth Avenue," Thomas F. Mulvoy, Jr., Boston Sunday Globe, July 24, 2005, City Weekly, p. 2. (Charles Brigham, architect).

• National Register of Historic District, 8/14/1973, National Park Service #73001948.

• "Burrage House: Study Report," Boston Landmarks Commission, City of Boston, 2002 http://www.cityofboston.gov/environment/pdfs/burrage.pdf

• Building Permit, City of Boston, 4/29/1899, Permit 254 of 1899.

• "Charles Brigham," MacMillan Encyclopedia of Architects, Adolph Placzek, entry written by Margaret Henderson Floyd, 1982, p. 288-9 (Burrage House, Commonwealth Ave., 1899, Charles Brigham architect).

• "A Terra Cotta Cornerstone for Copley Square: Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 1870-1876, by Sturgis & Brigham." Margaret Henderson Floyd, Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians, May, 1973, fn. 30.

• Back Bay Historic District, 9/3/1966.

• "A New England Architect and His Work," Oscar Fay Adams, New England Magazine, June, 1907 (Charles Brigham, architect). http://www.millicentlibrary.org/brigham.htm

• Boston Landmark, 1/28/2003

Images

2010, Hereford Street facade

2010, bay on Hereford Street facade

2010, Hereford Street facade

2010, Hereford Street facade and bay detail

2010, detail of bay pinnacles, dormer, chimneys on Hereford Street facade

2010, detail of bay pinnacles, dormer, chimneys on Hereford Street facade

2010, rear facade

2010, stained glass on rear facade

2010, conservatory

2010, conservatory detail

2010, Hereford Street and rear facades

2010, Hereford Street and rear facades, detail of upper stories

2010, window detail on Hereford Street facade

Great hall detail

Entry vestibule

Vestibule plaque

Library ceiling

Library ceiling

Drawing room ceiling

Anteroom

Living room looking to conservatory

Living room ceiling and mouldings

Living room detail

Living room fireplace

Conservatory ceiling

Coral wall in conservatory, coffering, classical columns and other detail

Dining room looking into the conservatory (left)

Dining room pocket doors to conservatory

Dining room stained glass

Dining room panel detail

Great hall look to the main entry

Great hall showing apse and leaded glass display case

Great hall fireplace

Great hall apse detail

Great hall niche detail

Great hall apse floor detail

Great hall, detail of columns and apse

Great hall wood detail

Great hall ceiling detail

Great hall ceiling detail

2007 - Courtesy of Joyce Kelly

View up grand staircase to landing and three stained glass windows

Grand staircase detail

Grand staircase detail

Stained glass windows on landing between 1st and 2d floors, and light fixture

Grand staircase detail from landing to the second floor

Grand staircase detail from landing to the second floor

Second floor landing

Staircase to 3d floor

2010, front door and surround

2010, ground tile at front door

2007 - Courtesy of Joyce Kelly

2010, side window at front door

2010, vestibule and entry hall as seen through front door metal grate

Original library

Original library

Original dining room

Original living room

Original living room

2007 - Courtesy of Joyce Kelly

2007 - Courtesy of Joyce Kelly

2010, Hereford Street and rear facades

<<< Back to Design List

|

|

|